The LA Times poses the drug makers’ decision to expand their market as a purely humanitarian decision. According to them, “U.S. drug makers agreed Saturday to shell out $80 billion over the next 10 years to lower the cost of medication”–which sounds like a pure donation for a good cause. What they overlooked is the economic motivations behind it, which is to ultimately increase profits by enlarging the market.

I’ve discussed monopoly pricing in the higher-education market and the practice of segmentation in general to charge different buyers different prices for essentially the same thing. If a monopolist (because of patent laws, each pharmaceutical company is in effect a monopolist) attempts to get more customers by lowering its prices, it must sacrifice the much larger profits from those willing to pay more. Therefore, the traditional monopolist with no means of pricing differently for different customers always produces less than the profit-maximizing level under conditions of price segmentation.

In this case, they are introducing the price-segmentation scheme in an extremely sneaky way. It’s really no different than Apple selling (a non-redistributable version of) an iPod touch to me for $100 while selling the exact same device to Apple fans for $400; I would actually purchase an iPod touch for $100, which I am sure is above their cost of production, and this scheme allows them to sell the device to those who want it more, for more. To the LA Times, this would be Apple’s humanitarian effort to bring light to us all (like Microsoft employees) by giving us a “discount” when in fact this expands their market and allows them to charge many of their existing customers much more.

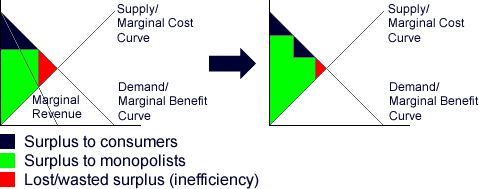

Although for Apple, figuring out who’s willing to spend how much is extremely difficult, the task is much easier for drug companies. People will spend as much as they can afford to purchase life-extending medicines–so to extend “discounts” to seniors for drugs not covered by Medicare is no altruistic deed. To illustrate the point, I’ve diagrammed the whole discussion in two simple standard supply-and-demand diagrams:

It is true that this overall system of pricing segmentation is socially more efficient than the incumbent system (the red triangle gets smaller), but that does not mean we consumers are better off. It’s questionable whether the consumers as a whole benefit from this. Although it is true that the seniors who could not afford the drugs previously do benefit–and that’s great–the drug companies are free to raise the price on the rest of us, so the entire concern regarding the cost of health care is definitely not alleviated.

The only group that’s sure to benefit from this is represented by the green: the monopolists. They can sell the drugs for more to those of us who can afford it, and they can now sell the drugs to those who they previously could not reach–at a good profit. That’s not to say that giving discounts to seniors who can’t afford the drugs at “normal” prices, or increasing incentives for biotech companies to invest are bad consequences; we–and especially the media–just need to be more careful in interpreting their actions.

Sometimes, a discount is anything but a discount. It’s a path to greater reach and profitability for the monopolists.