Religion, economics, mathematics and philosophy are just different perspectives on society and life. Although I have not discovered how I fit into the first perspective, the influences that latter three have had on me are obvious and many.

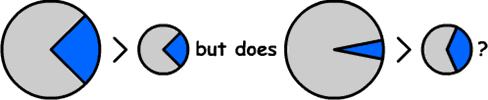

Two and half weeks ago on pi day (3/14 for those in the dark), when forced to reveal a “secret” that I thought would be interesting for others to know, I wrote on a piece of paper: “I have always told myself and others that I am a true utilitarian, but I don’t know how far I would sacrifice my own welfare for the benefit of the whole”; and I accompanied it with a helpful diagram (blue denotes my portion of the hypothetical “economic pie” and gray denotes others’):

(For those who are wondering: No, it was not intentional for me to draw a pie on pi day)

When there is an obvious contradiction between the welfare of the self and of the whole, problems arise (the Prisoners’ Dilemma, a scenario often discussed by game theory, is a common example). So what do I do when I am presented with an option that harms myself but benefits others (necessarily more than it hurts me)? What if the option harms others but benefits me (necessarily less than it hurts others)? A true utilitarian would be no less a utilitarian to himself than to his neighbor. But am I one?

Economics offers the solution: when the pie that provides for everyone becomes larger, systems of distribution can be arranged in a fashion such that everyone benefits more than before–when the rich get richer more than the poor get poorer, the rich can help the poor and both would still be better off, for example. Of course, the rich, after their generous deeds, are less well off economically than before, but often exchanges are reciprocal, so all involved will eventually benefit. Hence, ultimately, things can be arranged such that there is no conflict between a utilitarian perspective and one that prioritizes the welfare of the self over that of the whole.

Much of this is explained by game theory. The key is communication and cooperation among all those involved to achieve the most desirable outcome for all.

That is the conclusion one comes to when he has no external frame to adhere to–mainly religion, Christianity for example. What do you do? Please God. How? Believe in him and do “good” things. What things are good? Those that Jesus would approve. But what are they? Read the Bible. Huh?

Instead, the moral and ethical beliefs of people like me are based on welfare–doing things that are good for you, your community, your country, your planet. Does it matter if it’s not in the Bible? Not really–if it increases total welfare (global trade), then it’s good. If it decreases total welfare (War in Iraq), it’s bad. If it doesn’t affect others at all (whatever happens between two consenting adults), it doesn’t matter if you do it or not. Hence, by not having an easy reference to query, we are forced to produce an understanding of ethics that is more rational, based on the concept of total welfare.

How do you define your morals? What examples of goodness do you look up to? How have they influenced your beliefs and understandings?