Let’s take the following assumptions as given:

- Governments can’t be held accountable for keeping spending in check, so they need strict limits

- But badly-formulated limits can be damaging to the economy, especially during crises such as what we’re experiencing now

- Creating short-term deficits with infrastructure projects is necessary to buffer economic activity during slowdowns

- Running short-term surpluses with spending control is necessary to prevent overheating and inflation during boom periods

- Large long-term public debts hamper long-term economic growth by draining the total savings available for private investment

- Monetary policy (cutting rates, raising rates) can only do so much (for example, now that the interest rate is practically zero, the Fed can do very little to stem deflation)–so fiscal policy is necessary to smooth economic growth

- The important measure for the size of deficits is as a percentage of GDP, not an absolute value. That is, a 500 billion dollar deficit of a 10 Trillion dollar economy (5%) is worse than a 700 billion dollar deficit of a 20 trillion dollar economy (3.5%)

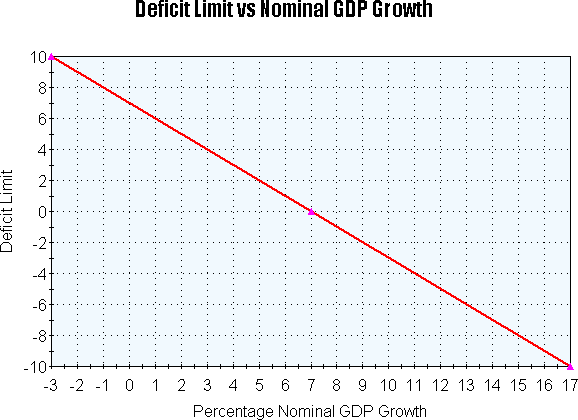

Hence I propose that the deficit limits be dynamically adjusted around the nominal growth rates of the same year (If the budget in question is for 2008, the limits will depend on the (projected) growth rate in 2008) according to the following schedule:

So now to answer a few questions:

- Why did I pick nominal instead of real GDP growth to base deficit limits on? Simple–because deficits are nominal and because nominal GDP growth rates also reflect inflation rates whereas the real growth rates do not. Therefore, when nominal growth rate is -3%, real growth rate is around -2% (the economy is contracting, but not as much as the nominal growth rate indicates because the CPI is coming down too), but when nominal growth rate is 17%, the real growth rate is around 5% (the economy is expanding, but it is overheating, with much of the growth sucked away by the double-digit inflation). By using nominal rate, deficits and surpluses are dynamically adjusted to fight both deflation and inflation, both of which are very damaging to long-term economic stability and growth.

- How did I pick the numbers? They aren’t completely arbitrary. From 1900 to 2007, the US economy grew at an annualized rate of 6.3% (nominal), so I picked a number just above the long-run average as a way of ensuring that the debt as a ratio of GDP won’t increase to infinity over the long run. (For the curious, if you look at the log graph for GDP growth, the line is straight, except for a couple bumps, suggesting that the growth rate will always tend to gravitate back to 6.3% a year) So why did I pick 7% instead of 6.5% or even 6.3%? This is an upper limit on how much more the government can spend than they collect, and as cynical as we can try to be, we can’t expect them to spend exactly the maximum every year. The extra 0.7% just adds a bit of flexibility.

-

So, what good does it do? I’m glad you asked. There are several:

- When the economy is contracting, people are looking for jobs and are willing to be hired for much less, so the government gets much more bang-for-the-buck by spending more during slowdowns (and vice versa for overheats, when costs are unreasonably high).

- When the economy is contracting, people aren’t spending as much–they’re saving for when the economy recovers. Great! Because that means interest rates are lower, and the government can buy more (since goods and services are cheaper) with less (since debt is also cheaper). Hence, we’ll be able to get stuff done more cheaply and stimulate the economy when it most needs it.

- If we assume the simplistic model that total consumption (or production) is private consumption (Say, of Joe buying a laptop) + public consumption (Uncle Sam fixing old bridges), we will always keep total consumption nearly smooth. If we further assume that private consumption is a function of total consumption (since every dollar spent is a dollar earned), the economy will hopefully never move to the extremes except in extreme circumstances like a world war (when we’ll be worrying about our survival rather than how much debt we owe to China)

- We don’t have to worry about our debt spiraling off into infinity, which seems to be what economic models predict right now.

- Congressmen will finally have a strict guideline for how much they can spend, especially those who have little sense of the value of money.

What do you think? Should we hold our congressmen accountable for all of the debt they’re passing to us?